Episode 19: Patenting Disney’s Lightsaber

In the latest episode of IP Practice Vlogs, it’s time for another design patent practical exercise.

In the latest episode of IP Practice Vlogs, it’s time for another design patent practical exercise. We previously did a design exercise on patenting Apple’s AirPods. This time we are going to patent the lightsaber. Watch for more on protecting color and variable designs.

Episode 17: Overcoming 101

The technological improvement test is used by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit to determine the issue of subject matter eligibility.

The technological improvement test is used by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit to determine the issue of subject matter eligibility. Of all the tests for a showing of something more or practical application – machine transformation, machine implementation, data transformation – technological improvement is probably the most popular and oft-used by applicants because it has the clearest standards. The technological improvement test used by the USPTO looks for a technological problem for which there is a technological solution and the claims recite a technological improvement therefor. Further, the prongs of the technological improvement test require framing the issues in terms of how a computer or a machine functions. In contrast, the machine transformation and the machine implementation tests are less clear as to the sufficiency of machine transformation or implementation to meet practical application. There is a great deal of nuance to the technological improvement test. Why are some computer-implemented inventions found to have technological improvement but others don’t? Watch for more.

Episode 18: Terminal Disclaimers and Cellect

The Federal Circuit basically confirmed in In re Cellect that terminal disclaimers can knock out patent term adjustment (PTA).

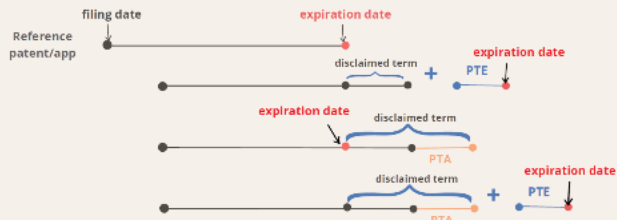

The Federal Circuit basically confirmed in In re Cellect that terminal disclaimers can knock out patent term adjustment (PTA). If you have patent term extension (PTE) and you filed a terminal disclaimer to overcome an obviousness-type double patenting (ODP) rejection, you can get the PTE term tacked onto the disclaimed date. However, in the case of PTA, the court says that PTA term gets added to the life of the patent first and then the terminal disclaimer goes into effect so that you have disclaimed the PTA term and any extended term such that the two patents now expire on the same date regardless of the PTA. In effect, terminal disclaimers may knock out PTA term.

What happens when you have both PTA and PTE? Your PTA may be eliminated but PTE can be added on after the disclaimed date.

Please watch our episode on Calculating Patent Term for a review of terminal disclaimers.

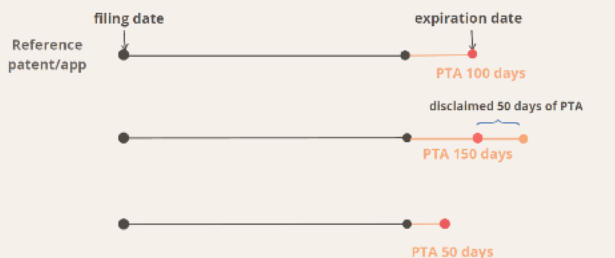

This decision does not mean you always lose all your PTAs due to filing a terminal disclaimer. Say your parent patent has a 20-year term from filing plus 100 days of PTA. The child patent issues with 150 days of PTA and a terminal disclaimer was necessary in the child patent. To calculate the PTAs of the child patent, you add the PTA days of the child patent (150 days) to the original expiration date of the parent’s. Then the terminal disclaimer goes into effect such that the two patents would expire on the same day. The child ends up losing only 50 days of PTA in this instance.

But what if the child patent only gets 50 days of PTA originally? In this instance, the terminal disclaimer does not affect the child’s 50 days of PTA, so it gets to keep those. But the child does not get an additional 50 days of PTA from the parent such that the two patents expire on the same date.

What happens if you don’t file a terminal disclaimer in a later filed patent in which the claims should have been rejected for ODP? Your rejected claims of the later filed patent are invalid and you have bupkis. That is what happened in Cellect. Cellect never got an ODP rejection during prosecution and, by the time it was raised during reexamination, all of the patents had expired. You can only file a terminal disclaimer during prosecution or during the life of the patent, such as in reexamination. And because Cellect never filed a terminal disclaimer, not only did they lose their PTAs, they lost all their rights because the claims are unpatentable due to ODP even though the ODP rejection was first raised during reexamination.

Just as a side note, I personally do not ever file terminal disclaimers until we have allowed claims. That is because claims are subject to change during prosecution such that the double patenting rejection can ultimately be rendered moot. ODP rejections are based on claims. In the Office Actions, you see these types of double patenting rejections show up as provisional rejections. They can be withdrawn as the claims are subject to change.

Filing Preemptive Disclaimers

The issue the Cellect decision leaves us with is that we now have to ask ourselves whether we should we be reviewing our entire patent portfolio to determine if we should be filing preemptive terminal disclaimers for cases that have not received an ODP rejection so that our claims do not end up getting invalidated during reexam as happened in this case.

Does that mean you and your client should try to identify all the potentially missed instances of ODP in light of Cellect? It is actually probably not feasible in most cases, depending on the size of your portfolio. However, ODP usually arises in cases of family patents or applications. So, you may want to flag all your families, both applications and granted patents, as potentially needing terminal disclaimers. The following suggestions are provided in light of the assumption that your client has already given you the go-ahead to file preemptive terminal disclaimers.

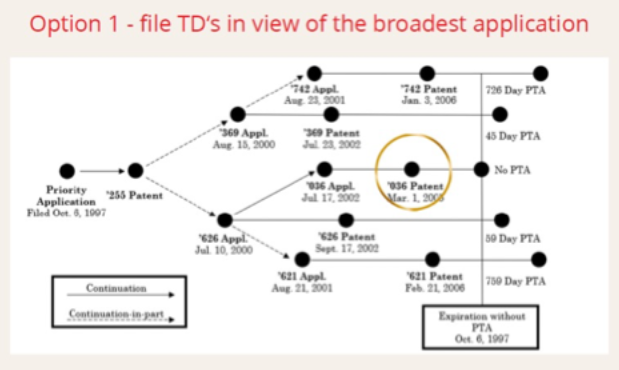

Disclaiming Relative to the Broadest Family Member

If it is clear which patent or application has the broadest claims (sometimes you and your client know when you wrote the claims that they are definitely the broadest of the family), you can consider filing terminal disclaimers just relative to the broadest family member. In Cellect’s case, the court found that the invalidation of all claims under ODP could be traced back to U.S. Patent No. 6,862,036 . Had they had the option, they could have tried to disclaim all the rejected claims in view of the ‘036 patent, which had no PTAs. So, if you want to make your life a little bit easier when you are dealing with a complicated family tree, you can consider filing terminal disclaimers in view of just the broadest potential reference.

Disclaiming Relative to the Earliest Filed Family Member

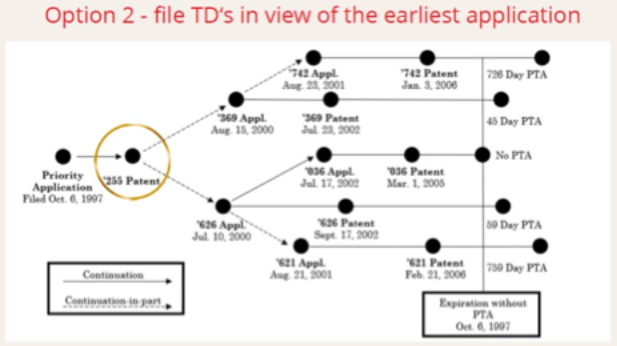

If it is not clear which is the broadest claim set, which is often the case, you can also consider filing terminal disclaimers in view of the earliest filed application. In Cellect’s case, the patents were all progeny of U.S. Patent No. 6,275,255 which also had no PTA. Cellect could have also disclaimed all their rejected claims in view of the main parent app, the ‘255 patent, had they had the option.

If your applications are still undergoing prosecution and have not yet issued, you do not know how many PTAs you will receive. But you can study the history of your applications to obtain a best guess as to which applications should receive more PTAs relative to the others and that can factor into your decision for selecting which reference application to be disclaimed relative to.

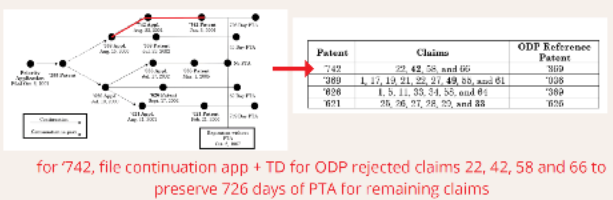

Utilizing Continuations to Preserve PTA

If your applications are still undergoing prosecution and you are facing an ODP rejection for an application for which you anticipate a lot of PTAs, you can file a continuation with a terminal disclaimer for the rejected claims so that you only disclaim term for the rejected claims. That way, you can preserve the PTAs for the remaining non-rejected claims. In Cellect, U.S. Patent 6,982,742 had four claims rejected in view of U.S. Patent 6,424,369. An option here would have been to cancel the claims 22, 42, 58 and 66 that were rejected in view of ODP and file a continuation covering just those claims along with a terminal disclaimer to overcome the ODP rejection. Now the rest of the rest of the claims of the ‘742 patent can go forward with the 726 days of PTA unaffected by the terminal disclaimer. This is in comparison to just filing a terminal disclaimer outright, in which case you would be losing all your PTAs for all your claims.

Reminder to Disclaim Term in the Later Filed Application

ODP can also arise in cases in which the relevant applications or patents are not part of the same family. When you have applications that do not share an earliest priority date, you should be filing terminal disclaimers in the later-filed application because that is the application having the term that is to be disclaimed. I have received ODP rejections only to realize the examiner raised the ODP rejection in the earlier filed case. They just saw two co-pending applications and decided to raise a double patenting rejection without looking at the dates. You should traverse the rejection in this instance and file a terminal disclaimer in the later-filed case because that is the case where you should be disclaiming term. Filing a terminal disclaimer in the earlier filed case is improper and would probably not shield you from invalidation. As we also learned from Cellect, equitable arguments to the tune of “we obviously were not trying to game the system, come on give us a break” don’t work.

Cellect might be taken up by an en banc panel. Who wants to see that happen? Tell us in the comments!

Episode 15: Understanding Extended European SearchReports

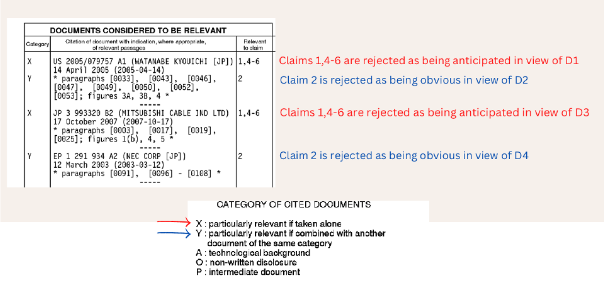

When you receive an EESR, you should turn towards the end and see which claims arerejected in view of the prior art and check to see if you might have any allowable subjectmatter.

When you receive an EESR, you should turn towards the end and see which claims are rejected in view of the prior art and check to see if you might have any allowable subject matter. All EESRs will include a chart after the substantive comments and that lists all the cited references corresponding to the claims that the references are being applied to. A reference marked “X” means it’s relevant when taken alone, which means it’s being used as an anticipatory reference. A reference marked “Y” means that reference that’s relevant if combined with another document.

In the sample below, we have claims 1 and 4-6 as being anticipated in view of the first reference. Claims 1 and 4-6 are also rejected as being anticipated by the third reference. Claim 2 is rejected as being obvious in view of the second reference, and quite possibly as being obvious over the combination of the second in view of the first reference. Claim 2 is also alternatively rejected as being obvious in view of the fourth reference, which is probably over the combination of the fourth in view of the third reference. Looking at this chart gives you a good overview of where your claims stand and which references you should pay attention to.

Two-Part Form

European examiners often ask applicants to amend the independent claims into this so-called two-part form. This is a formality matter that is basically untraversable.

It is in the applicant’s interest to not include environmental structure in part two because this section is supposed to have only what’s necessary for novelty. If you accidentally include too much environmental structure to give breadth to the point of novelty, then you’ve set a very low ceiling for yourself because you cannot go broader than your original presentation of the claims. At the same time, it also looks like you’re not supposed to be claiming environmental structure in the first part either.

So, what happens when you have environmental structure? You often need to claim environmental structure whether you’re talking about mechanical or software claims because you do that to give breadth and light to the claims. Say you have a mechanical claim in which you’re claiming a new transmission but the point of novelty is about how it’s fixed in the engine compartment. You have to claim some conventional parts of the transmission and some conventional parts of the vehicle to capture how the parts interact with each other in order to capture the point of novelty.

If you’re entering Europe on the basis of a U.S. application, or vice versa, you should probably advise your client to rewrite the claims upon entry into the different countries to place them in better condition for foreign examination. That is, if your client is going into Europe using a U.S. application, you can amend the claims to segregate the environmental features from the characterizing part so that you do not unduly limit the scope of novelty.

Claiming Beyond the Scope of Your Original Disclosure

Because terminal disclaimers make it such that the patent expires at the same time as the commonly owned patent, terminal disclaimers can obviate all your PTA days so that the patents expire on the same date. PTEs, in contrast, are explicitly meant to extend the term of the patent; terminal disclaimers cannot impact the duration of PTEs.

PTAs and Applicant Delay

You see these types of rejections way more in EESRs than in U.S. Office actions because of how the EPO interprets claims. Check out the example in the video where I talk about my own experience.

Practice tip. When you are writing your application to describe a method, do not describe the method as, “the method comprises steps A, B and C.”

Instead, try describing “The method comprises step A. The method can also further comprise step B. The method can also comprise step C.”

For an apparatus claim – “The apparatus comprises a gear. The apparatus can also comprise another gear. Then it can also comprise another gear.”

On top of this, you describe the method as comprising all the steps A, B and C in series or in any particular series. Also, the apparatus can comprise any one or more of the first, second and third gears either together or in other combinations. This way, you describe your inventive features both broadly and narrowly so that you have full support for different claim scopes.

Responding to an EESR

Applicants can submit amended claims as part of a Main Request with one or more Auxiliary Requests. These are all completely different sets of proposed claims that are separately considered but submitted in a single response. If your amendments in the Main Request are not successful, the examiner then has to consider the amendments in an Auxiliary Request if you submitted one. It’s almost like adding new claims for the examiner’s consideration. But adding new claims means more fees at some point. So Auxiliary Requests does not equate to adding new claims – it’s dressing the same set of claims up differently.

Episode 16: Petitioning the USPTO

As a rule of thumb, objections from the Office are petitionable and rejections from the Office are appealable.

As a rule of thumb, objections from the Office are petitionable and rejections from the Office are appealable. Rejections under Sections 101, 102 and 103 involve questions of law and therefore have to be appealed to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) as an ex parte appeal. But for everything else, if you have a dispute with the examiner that’s not going anywhere and the examiner isn’t withdrawing the objection – you petition those matters.

Therefore, you can petition drawing objections, objections to your specification or other formality objections. Another example is traversing an improper restriction requirement. You are required to elect a restriction even if you do not agree with the restriction in order to move prosecution forward, but you can traverse the restriction and you can petition the restriction if necessary. Means-plus-function interpretation of your claims is another petitionable matter. Remember, restrictions are not rejections and neither is a means-plus-function reading. So, you petition those matters.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) provides a list of petitionable matters that are categorized in terms of prosecution stage and whether the application has been allowed or issued.

Episode 13: Improving the Robustness of the US Patent System

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) would like public comments on how to update the 2019 Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) would like public comments on how to update the 2019 Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance. The agency is also seeking comments on how to improve the robustness of the patent system overall. This article/video is in (unofficial) response to both of these requests for comments.

Episode 14: Calculating Patent Term

After June 8, 1995, U.S. utility patent terms changed from 17 years from issuance to 20 years from filing to harmonize with the rest of the world under the Uruguay Rounds Agreement Act.

After June 8, 1995, U.S. utility patent terms changed from 17 years from issuance to 20 years from filing to harmonize with the rest of the world under the Uruguay Rounds Agreement Act. For design patents, after the Hague Agreement on May 13, 2015, design patent terms changed to from 14 years from issuance to 15 years from the date of grant/issuance.

In the United States, patent term is subject to the following: patent term adjustment (PTAs), patent term extension (PTEs) and terminal disclaimers. While many other countries also have PTAs and PTEs, terminal disclaimer practice exists only in the United States because we are the only country that issues judicially-created, non-statutory double patenting rejections.

Patent Term Adjustments and Patent Term Extensions

PTAs and PTEs both compensate for delays during prosecution of the patent.PTA compensates applicants for USPTO-caused delays, and is available to almost all utility patent applications. PTE compensates for delays caused by the regulatory review process before a product can be commercially marketed. PTEs mostly apply for pharmaceutical patents, as they are subject to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) review, which can take a long time. PTE is designed to extend the life of a patent because the applicant was not able to practice the invention during the regulatory review process, unlike other applications not subject to regulatory review, which the applicant can practice at any point during the pendency of their application before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

Terminal Disclaimers

Terminal disclaimers are filed to obviate double patenting rejections, in which an applicant’s claims are rejected in view of earlier filed claims by the same applicant in a separate application. For double patenting rejections, the pending claims are rejected either on the grounds of being obvious or not novel in view of the prior filed claims that are commonly owned. The idea is to prevent applicants from owning duplicate claims having different patent terms and effectively having an unduly long patent term over a particular claim scope.

With a terminal disclaimer, the applicant dedicates to the public the non-overlapping terminal term of the patent that received a double patenting rejection. The terminal disclaimer is recorded at the USPTO such that if the pending application would have had a term that surpassed the expiration of the prior filed patent, then that term is disclaimed, such that the two patents expire on the same date.

Applicants typically file these once the claims are basically in condition for allowance and all rejections have been overcome but for the double patenting rejection. By and large, I have found that applicants are willing to file a terminal disclaimer at this point to get their application allowed because they are tired of fighting and want to move on with their lives. But to those of you with a pharmaceutical client, meet the hill you’re going to die on!

Terminal Disclaimers on PTAs and PTEs

Because terminal disclaimers make it such that the patent expires at the same time as the commonly owned patent, terminal disclaimers can obviate all your PTA days so that the patents expire on the same date. PTEs, in contrast, are explicitly meant to extend the term of the patent; terminal disclaimers cannot impact the duration of PTEs.

PTAs and Applicant Delay

Because PTAs only compensate for prosecution delays caused by the Office, they will not compensate for delays caused by the applicant. Basically, applicant delay occurs when filing outside of the three-month statutory period (e.g., filing requests for extensions, or filing post-issuance or allowance).

One of the ways the applicant can hold up the pace of prosecution is by failing to timely submit information disclosure statements (IDS’s). You typically file an IDS when you file the application with references your client has provided or you found via a search, before prosecution begins. After prosecution begins, you are likely to file an IDS if your client filed the invention in several countries, and the corresponding foreign applications received office actions abroad that cited new or different references against those applications. Depending on what stage of prosecution you’re in, you may or may not have to make certain certification statements and submit fees.

Utilizing the Safe Harbor Period to Avoid Reduction in PTA

When you get one of these foreign office actions citing new relevant art that wasn’t previously considered, the applicant is entitled to a safe harbor period during which they can submit their IDS without risking any reduction to their PTA. That safe harbor is given when the applicant files the IDS within 30 days of receiving the foreign office action and applicant makes the safe harbor statements under 37 CFR 1.704(d).

Each item of information contained in the information disclosure statement was first cited in any communication from a patent office in a counterpart foreign or international application or from the Office, and this communication was not received by any individual designated in 37 CFR 1.56(c) more than thirty days prior to the filing of the information disclosure statement.

Each item of information contained in the information disclosure statement is a communication that was issued by a patent office in a counterpart foreign or international application or by the Office, and this communication was not received by any individual designated in 37 CFR 1.56(c) more than thirty days prior to the filing of the information disclosure statement.

These safe harbor statements are actually just like the certification statements on the SB/08 forms, except for one key difference – the certification statements on the IDS form says that the foreign office action came in no more than three months ago, whereas the safe harbor statements say that the foreign office action came within the past 30 days. So basically, applicant can file within three months of receiving the foreign office action to comply with the USPTO rules, but 30 days is a safe harbor in which you’re guaranteed to not get any reduction in PTAs.

All this really only matters after prosecution has already begun – that is, after you’ve received a first office action on the merits. Same with the certification statements – you don’t have to make them unless prosecution has begun because applicant cannot delay prosecution when prosecution has not started. And prosecution has started after Request for Continued Examination. So, even if prosecution has re-started, it has technically already started for the purposes of making these statements.

The USPTO recently proposed a rule change that applicants must fill out form PTO/SB/133 to submit the safe harbor statements. This proposed rule will likely go into effect, so be sure to submit that with your IDS within 30 days of the foreign office action to avoid reduction in PTAs.

Episode 11: The Copyright Claims Board

Claims Before the CCB

The CCB accepts three types of claims:

- Copyright infringement. Infringement occurs when a copyrighted work is reproduced, distributed, publicly performed or displayed, or made into a derivative work without the permission of the copyright owner, with no qualifying exception like fair use.

- Claims seeking a declaration of noninfringement. This is relief not for the owner of the copyright, but the party being accused or potentially accused of infringement. Say for example, a party gets a cease-and-desist letter threatening a copyright lawsuit, but that party doesn’t believe they’ve done anything wrong. They can ask the CCB for a declaration that is a determination that the accused party has no engaged in wrongdoing.

- Claims regarding misrepresentations when filing a “takedown” notice or a counter-notice under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). The DMCA allows for a “notice and takedown” procedure for removing infringing content from the internet in which a copyright owner sends a “takedown” notice to an online service provider. For example, a copyright owner can ask Comcast (an internet service provider) to take down a url that actually belongs to them. So, this third type of relief occurs when the alleged infringer feels that the DMCA claim included misrepresentations and can supposedly invalidate the takedown request.

Monetary Caps at CCB

At the CCB, all monetary damages are capped no matter the amount of actual damages the copyright owner suffered. In the CCB, you can seek either actual damages or statutory damages, but all of monetary damages are capped at $30,000 in each proceeding regardless. For example, you bring a case for infringement, you can be seeking both monetary damages for infringement at the same time you’re also attorney’s fees. All that is part of a single case that’s capped at $30,000.

If you’re seeking statutory damages, the cap for statutory damages is capped at $15,000 per work. So that’s $30,000 cap per case, and a $15,000 cap per work if you’re seeking statutory damages. If you’re seeking actual damages, looks like you can seek up to the $30,000 cap for a proceeding.

Damages for Registered versus Unregistered Works

The $15,000 statutory damages cap and the $30,000 total claim cap are for registered works. For unregistered works, the cap is much lower – it’s $7,500 per claim and $15,000 per proceeding.

Just as a reminder, copyright protection extends to creative works whether they are registered at the copyright office or not. Unregistered creative works are protected by copyright under common law. So, you can still presumably assert unregistered works. But, this is one of the benefits of registering – you get higher statutory damages at the CCB.

Contrast this with seeking statutory damages in federal court. Statutory damages in front of the federal court only extends to registered copyrights. If you have an unregistered work and you’re suing in federal court, you must seek actual damages, meaning you have to gather evidence and go through discovery, which greatly enhance the cost of bringing a copyright suit. On top of this, you still have to register your work in order to bring that suit for actual damages in federal court. That’s a key difference between federal court and the CCB – the CCB takes cases for unregistered works at the time you bring the case. However, the CCB does require that you have at least submitted an application at the Copyright Office at the time you bring your claim.

Reasons to Register Your Copyright

While you can seek statutory damages at the CCB for both registered and unregistered copyrights, your registered copyrights have a higher monetary cap, whether its actual or statutory damages you’re seeking. In federal court, you can seek statutory damages for registered works only. These are all reasons why you should register your copyright ASAP.

Small digression – another reason to register copyright is that a registered IP right expedites a takedown notice. Whether you’re trying to do a DMCA takedown or you’re informing an online marketplace (e.g., eBay or Amazon) to takedown something that you see that infringes your IP – you really do need to present a registered IP right. This goes for trademarks as well. If you see someone infringing your trademark on an online marketplace like Alibaba or Amazon – the platform will ask you for “proof of IP ownership.” You need to present a registered trademark in this instance. Trying to enforce common law rights in this notice and takedown context really doesn’t work.

Bringing a CCB Claim

When you bring your claim at the CCB, you will need to identify the category of the work of authorship (e.g., literary or dramatic work, musical work, architectural work, etc.) involved in your dispute.

On top of monetary damages, you can get an agreement to stop infringing activities. This is not an injunctive order like those you get at a real court, which comes with an enforcement mechanism. The CCB can order you to get along. But it can’t enforce it.

Smaller Claims and Attorneys’ Fees

The CCB is a small claims court that has an even smaller claims court embedded therein. For these smaller claims, damages, exclusive of attorneys’ fees, are capped at $5,000. If you go this route, your claim will be decided by a single Copyright Claims Officer instead of a three- person tribunal.

Regarding attorney’s fees at the CCB, you’re not likely to get them except in cases of bad faith or dishonest conduct. The loser pays the attorneys’ fees whether that loser was represented by an attorney or not. So, either claimant or respondent can be paying for attorneys’ fees. Attorneys’ fees are capped at $5,000. But for the losers who are not represented by an attorney and still being ordered to pay attorneys’ fees, that pro se loser only has to pay $2,500.

Other Key Features

- Statute of Limitations. The same statute of limitations applies for bringing a CCB as that for bringing a copyright case in a federal suit. The Copyright Act sets the statute of limitations at three years from the time of the activities involved in the claim – that’s three years from discovering infringement. You can’t present evidence of infringement that goes back longer than three years.

- Opting Out. Participation in CCB is completely voluntary for both claimants and respondents. Claimants can either choose to go to the CCB or to federal court. But not both obviously – you have to pick one. If you’re a respondent or a defendant, you can opt out of the CCB within a 60-day window after receiving a notice that the CCB claim has been filed.This is not my favorite feature about the CCB because if you’re a small pro se claimant and you file a CCB claim and the respondent knows you don’t have the means to pursue a federal court case, the respondent can just opt out of CCB and the claimant is effectively out of options. CCB is supposed to help the small guy right? Seems like the opt-out feature negates the benefits for small pro se claimants.

- Counterclaims. If you’re bringing a counterclaim it must be related to the original claim, obviously, just like all countersuits.

- Limits on Claims. There is a limit on the number of claims that any party can file in a single year and for the life of me I could not find what the limit is – it’s a secret. Do you know? Please comment.

- Legal Determinations Not Decisions. CCB determinations are not decisions. They have no legal precedence and are not binding on any future determinations or federal court proceedings.

- Determinations are Final. If you lose at the CCB, you can’t get a second bite at the apple and file your claim in federal court. If you lose, you lose forever.

Episode 12: Overcoming Obviousness Rejections

Did you know that the examiner bears the initial burden of proving a prima facie case of obviousness? You, the applicant, do not have any duty or burden to prove nonobviousness.

Did you know that the examiner bears the initial burden of proving a prima facie case of obviousness? You, the applicant, do not have any duty or burden to prove nonobviousness. Therefore, initially, the applicant has no obligation to present any secondary evidence of nonobviousness. It is only when the examiner has proven a prima facie case of obviousness that the burden shifts to the applicant.

Prima facie obviousness is a preponderance of the evidence standard. That is, the examiner has to weigh the evidence of the entire record (that includes your disclosure and all of the prior art references made of record) and find that there is more evidence in favor of a finding of obviousness than evidence presented against it. In other words, that it is more probable to be obvious than not obvious based on all the evidence considered.

After weighing the evidence and finding that the invention is more probable than not to be obvious, the examiner must then present a rationale linking the evidence to a legal conclusion of obviousness. Have you ever received a rationale with no evidence? I have. Examiner rationales for obviousness rarely, from my experience, include links to proof—I’m sure you have experienced this as well. Often, the rationale links to nothing and you simply receive the rationale and conclusion: your claims have been rejected, have a nice day.

When it comes to the applicant’s rebuttal (i.e., the examiner has met the burden and the burden has shifted), applicant can present evidence of secondary considerations. Presenting evidence of secondary considerations prematurely may constitute implicit admission that the examiner has met his/her burden. Secondary evidence includes evidence of commercial success, long felt but unsolved needs, failure of others and unexpected results. This type of evidence supports a finding of non-obviousness.

Remember, attorney arguments are not evidence. However, an affidavit from a person having ordinary skill in the art (your inventor, for instance) can be considered evidence. Also, when presenting evidence of commercial success to prove nonobviousness, you need a nexus between the commercially successful aspect of the product and your claim. That is, your claim has to claim the thing that is making you a lot of money in the marketplace.

Episode 9: Protecting Cleantech

The USPTO announced a new pilot program directed at accelerating examination procedure for applications claiming cleantech technology.

The USPTO announced a new pilot program directed at accelerating examination procedure for applications claiming cleantech technology. Under the Climate Change Mitigation Pilot Program, qualifying nonprovisional utility patent applications involving technologies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions will be advanced out of turn for examination, or accorded special status, until a first action on the merits. Typically, applicants wait up to a year and a half after initial filing of a patent application for a first office action on the merits. It looks like applicants do not have to wait that long under the new pilot program. In the USPTO’s press release, the agency states that this pilot program is part of their commitment to explore accelerated review of patent applications that pertain to environmental quality, energy conservation, development of renewable energy, greenhouse gas emission reduction, or other climate related topics.

Only non-continuing original utility nonprovisional applications qualify for this program. The applicant can claim the benefit of an earlier filing date to only one parent application that is either another U.S. nonprovisional application or a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) application designating the United States. For example, applicant cannot claim the benefit of a PCT application that claims the benefit of a foreign national application—for example, a PCT application that claims Paris Convention priority off of a Japanese application. If claiming the benefit of a PCT international application, that international application must have designated the USPTO as the receiving office. The application must also claim an invention directed to certain technologies that are designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Episode 10: Patenting the Airpods

The first thing you do when patenting anything, including a design, is to decide the scope of your claim.

The first thing you do when patenting anything, including a design, is to decide the scope of your claim. In design patents, your scope is determined by what you claim, what you show and what you describe. Claimed features are depicted by solid lines. Dashed lines depict unclaimed features that provide environmental context for your claimed features that are in solid lines.

The United States allows for partial designs, so take advantage of it when you can. When deciding your scope (that is, deciding your embodiments and what to depict in solid or dashed lines) you and your client may choose to proceed with more than one scope in order to best protect your product. So, in that case, you are filing with more than one embodiment. For the AirPods, we should definitely patent more than one embodiment as there are several ways to protect the essential ornamental features of this design.

Episode 7: Obviousness in Design Patents

While it may not be common to receive a prior art rejection for a design patent, it certainly can happen, especially if the design is broadly claimed.

While it may not be common to receive a prior art rejection for a design patent, it certainly can happen, especially if the design is broadly claimed. In utility patents, the issue of obviousness is an analysis of what a person having ordinary skill in the art would find to be obvious in light of the same or similar problem. When it comes to design patents, obviousness rests on the “ordinary observer” test, which is an analysis of the claimed design and its prior art seen as a whole instead of comparing the claimed design to the prior art design element by element. While the ordinary observer test requires a consideration of the design as a whole in the context of its environment features, the claim scope remains very important in terms of how the design will be examined.

When confronted with an obviousness rejection using a combination of references, the examiner has to present a primary reference, which is a single reference that contains basically the same visual impression as the claimed design. A primary reference cannot have substantial differences in the overall visual appearance, and it cannot need major modifications to create the similarity in overall visual appearance. Next, if a primary reference exists, the secondary reference is assessed to determine whether an ordinary designer would have modified the primary reference in view of the secondary reference to create an overall appearance that is the same as the claimed design.

So, when dealing with a combination of references, the main or primary reference actually has to be pretty darn close to the claimed design. In fact, it has to be basically the same as the claimed design, with no substantial differences, no major modifications needed. The secondary reference only compensates for the slight deficiencies of the primary reference.

Episode 8: Claiming Foreign Priority

There are several ways to claim foreign priority for a patent application. The first option is filing an international application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT).

There are several ways to claim foreign priority for a patent application. The first option is filing an international application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT). In order to utilize this option, at least one of the applicants has to be a national or a resident of a country that is a PCT Contracting State. Upon filing, the applicant picks a receiving office, which is a national patent office designated for receiving the PCT application. A competent receiving office belongs to a location in which one of the PCT applicants is entitled to file a PCT application. Each PCT member state has a competent receiving office for its residents and nationals. The International Bureau of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) also acts as a receiving office in which all applicants are entitled to file PCT applications. In that case, the applicant can file directly with WIPO. Thirty to 31 months after initial filing, the application then enters the national stage and the applicant can select the countries in which it would like to file.

The second option is to claim priority under the Paris Convention. Here, the applicant’s initial filing is with a domestic national office of a country that is a signatory to the Paris Convention Treaty. The applicant then has 12 months to claim priority off of the initial filing to go to another country’s national patent office.

The third option is a bit like a hybrid of a Paris Convention/PCT filing. In this case, the applicant can file the initial application in a domestic national office, just like in option two. The applicant then has 12 months to file a PCT international application that claims priority to the initial domestic filing. But in this case, the applicant has 30 to 31 months minus 12 months to go national stage. For example, the applicant has 18 to 19 months from the date of the PCT filing to go national stage if the applicant filed the PCT application 12 months after the original priority date. But if the applicant filed the PCT application only one month from the domestic priority application, the applicant then has 29 to 30 months from the PCT application filing date to go national stage.

It is important to remember that an applicant can file foreign priority off of a provisional application. Therefore, if the applicant is trying to claim foreign priority off of a domestic patent application, if that application has a provisional application, it is the date of the provisional application that sets the clock for these foreign filing deadlines, not the non-provisional application.

During the international stage of a PCT application, the first major event is that the applicant will get an Visit W3SchoolsInternational Search Report (ISR) from WIPO, which occurs at 16 months. Along with the ISR, the applicant also receives a written opinion (WO). In response to an ISR, the applicant can optionally file an Article 19 to amend the claims in view of the ISR. If the ISR provisionally allowed any claims, the applicant can use those claims to elect using the Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH) during national stage which expedites the national stage examination. Say if the ISR does not allow the independent claim but deems some of dependent claims as containing allowable subject matter, the applicant can file an Article 19 to accept the allowable subject matter to then go PPH upon national stage to pursue the scope of the amended independent claim. At this stage, the applicant is restricted to amending only the claims.

At 22 months after filing a PCT application, the applicant can elect for further examination and demand Chapter II. Imagine a scenario in which the applicant did not receive any allowable subject matter in the ISR but saw a path for receiving allowable subject matter via an Article 19 amendment; the applicant can then Demand Chapter II in an attempt to get allowable subject matter in the Office of First Filing (OFF) to be able to utilize the PPH when entering the national stage. Optionally, the applicant can file Chapter II with an Article 34 in order to further amend the claims and skip filing an Article 19 amendment altogether. Unlike Article 19, in which the applicant can only amend the claims, the applicant can amend the claims and the disclosure (that is the drawings and specification) with an Article 34. Please see guidance on filing Article 19 and 34 amendments here.

Twenty-eight months after filing a PCT application, the applicant receives an International Preliminary Report on Patentability II (IPRP II), which takes into account the Chapter 34 amendments. The applicant can find out in the IPRP II if they received any allowable subject matter for PPH purposes that were not granted in the ISR.

PPH speeds up the examination process for an application that has corresponding applications filed in participating intellectual property offices. Under PPH, participating patent offices have agreed that when an applicant receives a ruling from an OFF allowing at least one claim, the applicant may request fast track examination of corresponding claim(s) in a corresponding patent application that is pending in a second patent office. Keep in mind that accelerating prosecution also means accelerating due dates for fees – issues fees, maintenance fees, attorneys’ fees. So, make sure to prepare your IP budget accordingly.

Episode 5: Intended Use Claims

Your claim preamble is more likely to be limiting when you’re dealing with a method claim versus an apparatus claim.

Your claim preamble is more likely to be limiting when you’re dealing with a method claim versus an apparatus claim. In Cochlear Bone Anchored v. Oticon Medical AB, Cochlear’s claim recited a hearing aid apparatus “for rehabilitation of unilateral hearing loss” in the preamble. Cochlear was challenged at inter partes review (IPR) where Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) found the preamble term “for rehabilitation of unilateral hearing loss” did not limit the scope of the claims. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit upheld the Board’s ruling, expressly finding that the statement of intended use is not limiting because the preamble did not furnish additional structure that was recited in the body of the claims. Primarily, the court found that the term “rehabilitation of unilateral hearing loss” was not suggestive of a particular type of hearing aid having a specific type of structure. The intended use of rehabilitating unilateral hearing loss can be considered to describe the use of hearing aids conventionally and not any specific type of hearing aid.

Looking at a method claim in Eli Lilly and Co. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Teva’s claims recited “a method for reducing of or treating” a symptom in an individual. The claims further recited that the method comprises an “effective amount” of a particular compound in the body of the claims. In this IPR, the PTAB found that the preambles are limiting to the extent that the recitation of intended use gave breadth and light, and therefore meaning, to the claimed “effective amount”. That is, the court found that preambles can limit the scope of the claims when the claims would not read on, for example, the performance of the same method step to treat other conditions.

The Federal Circuit further found that because method claims are ultimately directed to what the method does, statements of intended use in method claims can be limiting even if the statement of intended use is in the preamble. Here, Teva’s intended use for treating a headache as recited in the preamble includes clearly denotes that the claim is a method for treating symptoms “in an individual”—i.e., an individual who is suffering from those symptoms—by administering “to the individual” an “effective amount” to treat those symptoms.

Episode 6: Patent Eligibility of AI

When the original patent laws were drafted, lawmakers did not anticipate that one day we might have machines with decision-making capabilities that would mirror that of humans.

When the original patent laws were drafted, lawmakers did not anticipate that one day we might have machines with decision-making capabilities that would mirror that of humans. As a result, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), the European Patent Office (EPO) and the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) all have subject matter eligibility restrictions with respect to mental processes and patenting tasks that a human can perform, particularly what a human mind can perform, which includes processing information and data and making decisions based on said information and data. The idea is to prevent the patent system from being abused in this way. But, in view of the new technologies emerging in the field of AI, each of these offices have attempted to update their examination procedure to at best try to capture some of this subject matter.

The CNIPA prohibits patenting methods for mental activities. Recently, the CNIPA issued Draft Examination Guidelines Examination Guidelines on examining inventions related to the improvement of algorithms for artificial intelligence (such as deep learning, classification and clustering and big data processing). When looking for a “technical solution” that can render machine intelligence patentable, the CNIPA proposes looking at improvements to algorithms and big data processing, whether the algorithms have a specific technical relationship with the internal structure of the computer system, and/or improvements to hardware computing efficiency or execution effect. The CNIPA considers improvements to data storage size, data transmission rate and hardware processing speed as evidence of a technical solution required for patentability.

In March of this year, the EPO’s 2022 Guidelines for Examination came into effect, which state explicitly, “[a] mathematical method may contribute to the technical character of an invention, i.e. contribute to producing a technical effect that serves a technical purpose, by its application to a field of technology and/or by being adapted to a specific technical implementation.” The EPO is going so far as to explicitly state that mathematical formulas can be patentable if used in specific technical implementation. Specific examples of improvements to technical effect include efficient use of computer storage capacity or network bandwidth. EPO has published a series of examples of mathematical formulas that contribute to a showing of technical effect.

Episode 3 – Writing Strong Patents

When it comes to the matter of Section 101 subject matter eligibility, the USPTO and the Federal Circuit diverge somewhat in their analysis, specifically in their consideration of what constitutes an “abstract idea.”

When it comes to the matter of Section 101 subject matter eligibility, the USPTO and the Federal Circuit diverge somewhat in their analysis, specifically in their consideration of what constitutes an “abstract idea.”

Our modern-day concept of “abstract idea” is shaped by the Supreme Court’s ruling in Alice v. CLS Bank in 2014. The USPTO and the Federal Circuit both operate under the Alice doctrine of “abstract idea” when it comes to assessing subject matter eligibility, particularly when it comes to software patents. Alice requires that an “abstract idea” has “something more” than what is well-understood, routine and conventional in order to be patent eligible.

In 2019, the USPTO issued Guidelines which illuminated what constitutes “something more”, basically requiring a practical application of the abstract idea. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) has found that a practical application is demonstrated by showing a technical improvement. Under the USPTO’s approach, a “technical improvement” is an improvement to a machine or the functioning of a machine, designating a series of precedential or informative opinions on this matter. These decisions strongly emphasize that technical improvements should be improvements to machines, such as the improved functioning of MR tomography, or improving a catheter navigation system. However, improving the method of fitting a golf club (i.e., improving user friendliness) is not improving a machine. Improving a life cycle workflow is not improving a machine. The PTAB also assesses whether the claimed method or structure can be integrated with some kind of special purpose machine. “Integration” with a special purpose machine means that the claimed function cannot be performed by mental processes alone (e.g., the applicant has disclosed and is claiming computer-implemented algorithms and processes that cannot be accomplished by a human).

The Federal Circuit, being a court, is not bound by the USPTO’s agency Guidelines. There is no practical application analysis at the Federal Circuit. Rather, the court tends to look at whether there is an improvement. The Federal Circuit’s analysis of Section 101 is much closer to the well-understood, routine, conventional test of Alice. The USPTO, however, has tried to focus much more on practical application of a technical improvement. It is important to keep both of these approaches in mind when drafting your application.

Episode 4: Means-Plus-Function

A means-plus-function limitation is a functional limitation that claims function without structure. The claimed element presented for prosecution is pure function and not structure.

A means-plus-function limitation is a functional limitation that claims function without structure. The claimed element presented for prosecution is pure function and not structure. This type of claiming is used often with software patents, which recite function via a series of computer implemented steps to carry out a means. The test for definiteness under a means-plus-function context is whether there is sufficient corresponding structure in the specification that links the structure in the specification to the function in the claim.

So, what’s good patent practice? Make sure every one of your claims is in the specification! Start with the claims; have them be the groundwork for your application. And have an algorithm! Drawings are a good thing.

Episode 1:

The IP Practice Vlogs were born during Covid.

The IP Practice Vlogs were born during Covid.

Being unable to travel, we decided to start a video series to keep our clients informed of major trends and updates in the US intellectual property space. We hope you find this video series interesting and informative. From all of us at Global IP Counselors, thank you for watching.

Episode 2: The DSMER Program

Under the new Deferred Subject Matter Eligibility (DSMER) program, eligible applicants who receive a subject matter eligibility rejection with

Under the new Deferred Subject Matter Eligibility (DSMER) program, eligible applicants who receive a subject matter eligibility rejection with prior art rejection(s) or indefiniteness rejection(s) can defer substantively responding to the Section 101 rejection until all other rejections have been withdrawn. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) will notify eligible applicants in the first Office Action on the merits. The applicant can then choose to participate in the program by filling out a form paragraph.

The DSMER program is a limited waiver on responding to Section 101 rejections, meaning the applicant does not have to present evidence, arguments or amendments to overcome the Section 101 rejection. The applicant needs to only address the Section 101 rejection by referencing the applicant’s participation in this pilot program.

The limited waiver lasts until the occurrence of the earlier of two events: 1) final disposition of the pending application, or 2) the withdrawal or obviation of all other outstanding rejections.

“Final disposition” occurs upon the earliest of the following:

- A Notice of Allowance

- A final Office Action

- RCE

- Notice of Appeal, or

- Abandonment

“Withdrawal or obviation of other outstanding rejections” occurs when the applicant has successfully overcome all non-Section 101 rejections such that the Section 101 rejection is the only rejection remaining. At this point, the applicant is obligated to substantively respond to the Section 101 rejection.

IP Practice Vlogs by Global IP Counselors™ is a series of practice videos for the US IP practitioner.

Each video is designed to be under ten minutes in length with topics on practicing before the USPTO and the Federal Circuit. Additionally, the series brings to light key differences in prosecution practice before the USPTO versus the other major patent offices around the world, particularly with respect to critical emerging technologies, such as AI, robotics, big data and cryptocurrency. The IP Practice Vlogs are co-published by IPWatchdog, the largest intellectual property publication in the world, where you can find our episodes along with an accompanying article with hyperlinks to our sources.

1. Webinars published on this website are published as a service to the public and are not and should not be considered to be legal advice.

2. No attorney-client relationship will be established by inquiring about the content of these webinars. The information in these webinars is provided with the understanding that the providing of such information does not constitute the rendering of legal advice or other professional advice. Your use of these webinars does not create any attorney-client relationship. Information received from these webinars should not be relied upon or used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors.